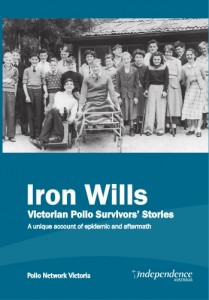

Iron Wills – Polio Network Victoria

Victorian Polio Survivors’ Stories

Victorian Polio Survivors’ Stories

A unique account of epidemic and aftermath

Published: 2012. 110 pp.

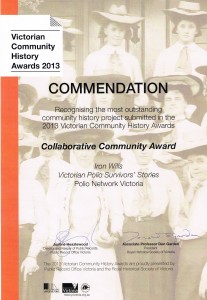

“Iron Wills” began as a project of the Polio Advisory Committee in 2009, when entries were collected and selected by former polio community officer Mary-ann Liethof and PAC member Margaret Cooper.

It was completed and published by the Polio Reference Group and is available from Polio Network Victoria.

This book is dedicated to all those touched by polio: young people, parents, siblings, extended family members and friends, doctors, nurses, splint makers, and physios, who made supreme efforts to get us through.

Although it was inevitable given the impact of the virus, to our dismay the battle is on again and a new generation is called to arms.

Many did not survive the illness and we salute them.

It is easy to forget what a vicious enemy the polio virus is. I can well remember summers as a schoolboy when my mother would not let me go to the movies or the swimming pool for fear of catching polio. I can also remember a wonderful sense of elation as a medical student when the great Australian virologist, Sir Macfarlane Burnet, just back from America, lectured to us about the new polio vaccine about to be perfected. Through the great work of Dr Val Bazeley of the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Australia in 1956 was one of the first countries to have the vaccine available, and the disease was conquered with amazing speed.

Young Australians have little sense of what those summer epidemics were like. But all of us have in our midst those over-fifties, men and women with iron wills, who are the polio survivors. This wonderful short book is their story.

Iron Wills, Victorian Polio Survivors’ Stories, produced by Polio Network Victoria in its 25th year, begins with a useful description of poliomyelitis, its history, its epidemiology, its prevention, its treatment and some of the great personalities involved. Then the book outlines the origins and aims of the Polio Network uniting the various polio support groups and allowing some hundreds of polio survivors to give one another mutual succour. But the main part of the book consists of wonderful stories: the lives and activities, the reflections and the poems, the photos and philosophies of an amazing group of polio survivors. These are stories of courage and resilience, of adaptability and optimism, of patience and achievement. A current of life-affirming strength and will runs through the narrative, amply justifying the book’s title.

We also learn a little about Post-Polio Syndrome, that totally unfair complication hitting 25 to 40% of polio victims many years after the original attack. The syndrome involves new weakening in muscles previously affected, accompanied by fatigue and frequently pain. It is very slowly progressive and hard to treat, though non-fatiguing exercise of the affected muscles can help in some cases. This extra burden adds materially to previous disability.

And now, in late 2012, the enemy at last seems on the brink of capitulation. The polio virus persists in only four countries, Nigeria, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Chad, and total global eradication should be achieved in a year or two. Such is the power of vaccines, but the triumph comes too late for the heroes and heroines of this book. Iron Wills deserves a wide readership, not just because it shows the power of the human spirit, but also because it is a reminder that one should not take microbes for granted. I want every anti-vaccine activist to read it and to think about the implications had the vaccine been discovered earlier. I also want every politician to read it and to ponder what an investment medical research represents. It has been a privilege to review what iron wills can achieve.

Foreword

Sir Gustav Nossal

Professor Emeritus

The University of Melbourne