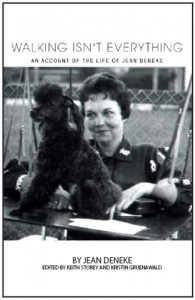

Walking Isn’t Everything: An Account of the Life of Jean Denecke

Edited by Kristin Gruenewald and Keith Storey

Edited by Kristin Gruenewald and Keith Storey

Oshawa: Crystal Dreams Publishing, 2008. 217 pp.

Available: Amazon

An Ordinary Life with Polio

Jean Denecke’s account of her encounter with polio and her subsequent life dealing with permanent disabilities emphasizes the ordinariness of her experiences. As she puts it, “except for my physical condition, I feel that I lead a perfectly normal life” (p. 16). Denecke wrote the book in the mid-1950s, approximately eight years after contracting polio in 1946 when she was twenty-nine. Denecke died in 1969 and the memoir is edited by her daughter Kris Gruenawald and nephew Keith Story. The editors do not explain the extent of their editing, but the text appears to be the one Denecke wrote in the early 1950s. She submitted it to several publishers, but she did not made the suggested revisions and it remained unpublished.

Denecke begins her memoir by recounting the onset of polio and her trip to the hospital. Once in the hospital, she found it increasingly difficult to breathe and was eventually placed in an iron lung. Unlike many polio narratives that emphasize the fear and anxiety about iron lungs, Denecke seems not to have had a powerful psychological response to being placed in the device. Her straightforward account of the time spent in the iron lung and in the hospital lacks the drama of many polio narratives. Her time of difficulty came later. As she began to recover, she acknowledged her fears about the future, and admitted that at her lowest point psychologically she wanted to commit suicide. Denecke had even decided that she would accomplish the deed using rat poison that she would have her husband bring to the hospital. Although the psychological problems apparently persisted even after Denecke returned home, she provides few details about her feelings, or about how she resolved them and decided to get on with her life. She does credit a chiropractor, who came to her home to provide massage and therapy, with helping her overcome the psychological issues.

Much of the memoir describes her four-month stay at the polio rehabilitation facility at Warm Springs, Georgia. She credits the resort-like social atmosphere with helping to restore her desire and determination to live a good life. Equally important, the therapists, brace- and appliance-makers, and wheelchair specialists provided her with the ability to sit up, to use a wheelchair, and to use her hands with the aid of specially constructed slings. Among other things, the experience at Warm Springs helped her to come to terms with the reality that she would never walk again, and to be grateful for the things she could do.

In the account of her life at home, both before and after her return from Warm Springs, Denecke stresses the ways in which she and her family, especially her husband and her daughter, found ways to create something approaching a normal life. Although she acknowledges challenges and difficulties, the emphasis is always on what worked. Part of her purpose in writing the book was to show other polio survivors what it is possible to achieve with hard work, a willing family and friends, and some imagination. The difficulty of finding good, reliable help ranked high among the challenges Denecke and her family faced. Here and there in the narrative Denecke suggests some of the continuing psychological issues that she and the family faced, but at no time does she reveal much about their nature or how they were addressed. She credits Harry, her husband, with making it possible for her to live at home and be an effective wife and mother, but we get little sense of their relationship or of the burdens that Harry assumed when his wife contracted polio. The narrative ends with a short account of setting up an in-home business. Denecke established a baby-sitting registry in 1954 and ran it successfully and profitably until her death from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1969. The book also includes an appendix with graphs on the occurrence of polio in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s, the twentieth anniversary program brochure of Warm Springs, and a brief biography of Jean Denecke by her daughter.

Denecke’s Walking Isn’t Everything clearly belongs to what Amy Fairchild has called the first wave of polio narratives. These narratives, written in the forties and fifties, take a generally upbeat approach to the experience of polio and of living with a permanent disability. Even when they acknowledge difficulties, as Denecke does, these first-wave authors tend to stress overcoming them and living a relatively normal life under the circumstances. Fairchild also notes that these narratives are typically reticent about psychological issues for both survivor and family, about sexuality, and about relations between husband and wife or parents and children [1]. Published in 2010, but written in the mid-1950s, Denecke’s book is a good example of a 1950s polio memoir. Denecke’s emphasis on the ordinariness of her extraordinary situation is a good reminder of a time when many polio survivors focused primarily on what they could do and on taking up once again the life interrupted by disease and disability.

Note

[1] Amy L Fairchild, “The Polio Narratives: Dialogues with FDR”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75 (2001): 491-492.

Review by: Daniel J Wilson. Review of Denecke, Jean, Walking Isn’t Everything. H-Disability, H-Net Reviews. August, 2010.